For Jeff King: Global Warming

>> Thursday, June 17, 2010

Jeff asked: Is global warming valid; is it really true in your mind?

Yes. But let me clarify.

The term, "global warming" is probably accurate for the long term. In the shorter term, the term "global climate change" is probably more appropriate because the process isn't simple or readily predictable.

But do I think humans are in the process of making a profound (and potentially somewhat irreversible) change to the world's climate (and more)? Yes. And I don't know a reputable scientist who doubts it. In the scientific community, what has fuzz on it is not what carbon does to the climate, but how fast it does it, how much is irreversible, and exactly what the impacts are going to be if we (a) stop now and (b) continue to pump carbon dioxide into the atmosphere as if there were no repercussions. The question really isn't, will our children and our children's children pay a price for our excesses? They will. The question is, "How much and which children?"

Right now, for instance, I don't think anyone contemplates a runaway greenhouse like Venus because, hey, that would really kill us all. Even our direst predictions don't take us there (though I might add that all our greenhouse models can't get us to how hot Venus is, so clearly they aren't complete and can underpredict the effects).

But there are a few facts that people who walk into the discussion should acknowledge. First, the greenhouse effect is a demonstrable phenomena. Large amounts of carbon in a simple system can be shown to increase the temperature by absorbing more of the energy from the sun. (See explanation here.) Atmospheric carbon dioxide (and other gases like methane) change the absorption of energy by the sun. That's not in question.

However, unlike a science experiment, the world's atmospheric system is very complex. So there isn't a direct simple correlation to the tons of carbon we pump into the atmosphere to direct temperature change. Why?

There are a number of factors we know about. For one thing, warmer oceans and plant life absorb carbon. However, we don't know whether that can happen indefinitely or if we'll reach a saturation level and stop. And more carbon in the ocean means a greater acidity, which affects a huge and delicate ecosystem. We don't know the repercussions for the water world entirely, but we know it can affect coral reefs and other coastal waters. Even if we didn't have a responsibility to preserve our oceans, we should bear in mind how many millions, no billions, of people depend on the oceans for sustenance.

Warmer temperatures might affect the strength and prevalence of storms, or the extremes of temperatures in the seasons (as might be expected when putting more energy into a chaotic system - you get some unpredictable results). It melts glaciers which uses up some of that energy, but the reduction in ice surface coverage and increases in airborn water vapor (water vapor is another greenhouse gas) increases the energy absorbed even more (as ice reflects more energy away than land or water).

But that sounds like speculation. And, to an extent, it is. We can't tell for certain, what changes will happen, how fast, or what the long term effects will be.

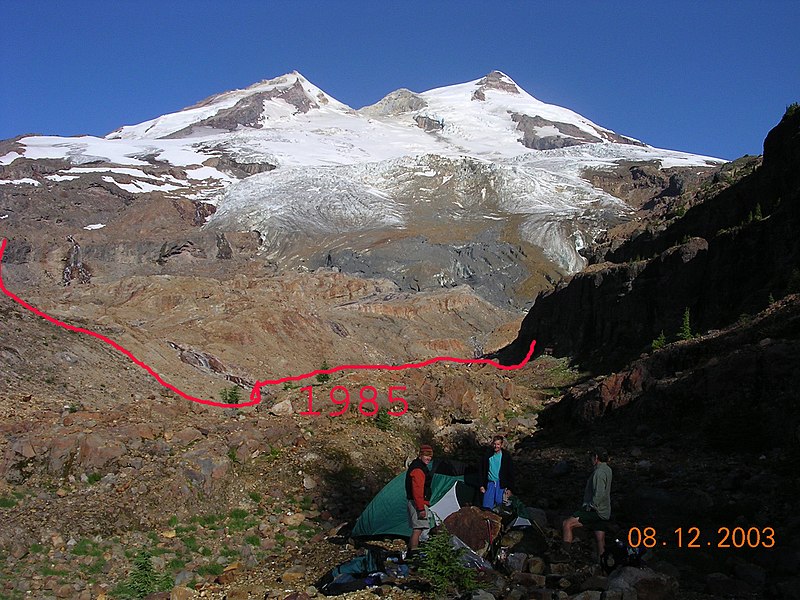

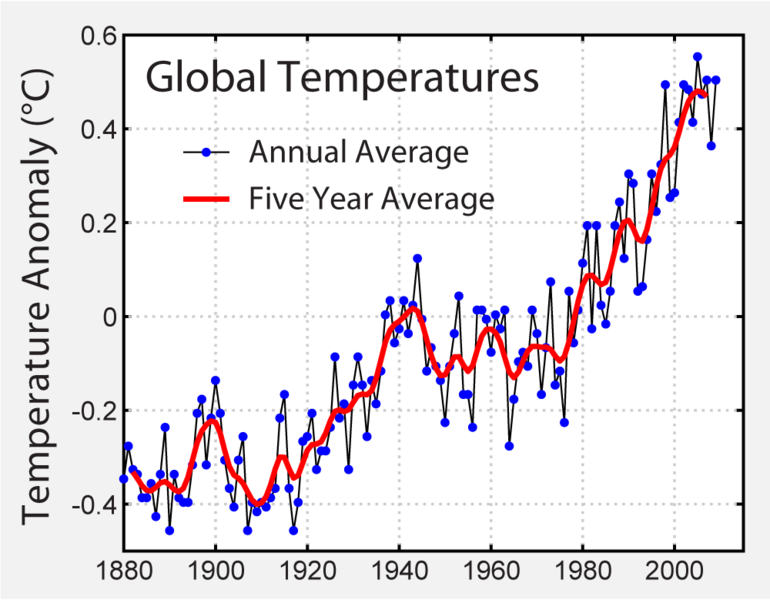

So, why worry? Well, because not knowing how bad it's going to be doesn't mean that changes aren't coming. We know they are because some are here. Glacier retreat is demonstrable arctic ice is at some of it's lowest measured levels. Average global temperature has been increasing. Droughts the past few years have been some of the worst in recorded history - as have been a number of floods and storms. Most of the predictions, even the most dire, about ice loss fifteen years ago, for instance, have turned out to underpredict the actual loss seen, particularly in South America and Greenland.

Glacier melt has been noted as potentially leading to higher sea levels, but the effects are more chilling than that. The same melt that can raise sea levels, can also cause devastating flooding (as glaciers are frequently the sources for rivers) in the short term, but worse, also potentially dry up rivers that literally billions of people depend on for water. That's not hype. It's happening in the Andes right now.

In fact, given the data that's available, I don't think one can reasonably doubt the fact that we have affected the climate. But I'm not sure anyone knows for sure how far-reaching those changes are going to be and when we're going to step in to stop our part in it.

I'm not frightened by the alarmists on this, with their "worst case scenarios." What frightens me is that most of the worst ones I've heard have fallen short of the reality we've seen. Many of the changes we're seeing today, no one expected for another fifteen years.